I’ve decided to resuscitate my semi-sensible blog for an occasion. It’s fifty years this weekend since the publication of the Top Twenty that I used to swear by. My sister Clare and I used to debate the merits and demerits of other weeks in the pop-pickers’ calendar, but this one came out top, always, and despite its rather predictable inclusion of some very serious and far from winsome schmaltz.

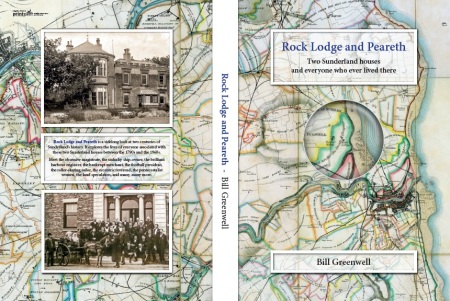

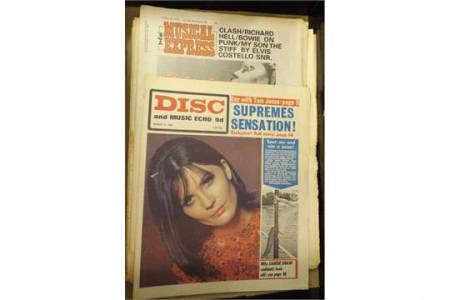

Pop music (it was always called that in 1966, there being no fault-line at the stage with ‘rock music’) has been in my bloodstream since I was about nine (early 1962), and it’s too late to be apologetic. At the boarding school in North Yorkshire where I was happily incarcerated at that time, we had a music teacher called Iain M. Christelow, a good man who urged us to choose between Beethoven and Doug Sheldon (‘I saw Linda Yesterday’). It was an unfair contest, really, and I picked Sheldon, and stuck with the charts in which he had made a fleeting appearance for longer than I should done. The consequence is that my head is filled with bits and pieces of factoid about pop music. The inside of my brain is papered with back issues of Disc and Music Echo, NME, Melodymaker and Record Mirror, which all had different charts. The one I am using (and perhaps the most influential on the BBC, who cherry-picked the lot of them until 1969) is Record Mirror, which may account for the slight discrepancies with my memory. But there again, the holes in my memory need no scapegoats.

I once read that musical taste is fixed at the age of fourteen. This strikes me as true, as I have a weakness for the music of 1966 and 1967, and started the old-man-complaining routine about deteriorating standards about halfway through 1968. When the chart below came out (September 3rd 1966) came out, I was fourteen. In fact, it was my fourteenth birthday. We were on holiday – at Belford, in Northumberland, in a hotel. We were there a week before moving to Peebles. It was the first year we had not been to Bamburgh (1957 to 1965), where we had previously rented a house in South Victoria Terrace every year. My mum had declined to cook for the family on holiday, and hence the hotel. It was not a great idea. She was a better cook than the hotel kitchen, and it was cramped – when we got back from Bamburgh and Seahouses (where they had a jukebox), as we did each day.

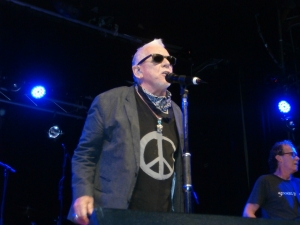

Before we get to the twenty, it’s time to select a few of the ‘bubbling under’ records that had been released, and which were heading for the top, or thereabouts. (Where I can, I’ve added a Youtube link to the title.) One of these was The Spencer Davis Group’s When I Come Home. This in fact the first time a Steve Winwood song had entered the charts – it was co-written by him with the Jamaican singer Jackie Edwards (who had written the group’s first two hits, Keep On Running and Somebody Help Me). Unlike later hits like Gimme Some Lovin’ and I’m A Man, Winwood was featured principally on guitar, not organ. He was only seventeen, and used to appear in lists of guitarists, in a way now forgotten. One of the pleasures was the way Davis’s voice complemented Winwood’s (Winwood is doing a very clever copy of Ray Charles. The reason he was so good at rhythm and blues – a phrase that now has a totally different meaning – is that he actually sounded like the American soul singers he admired.) I have seen Davis himself do this song within the last decade, and the power of his voice shouldn’t be forgotten.

Also in the ante-chamber were The Supremes and You Can’t Hurry Love. This was a Holland-Dozier-Holland breakthrough for Ross, Wilson and Ballard, who had already had a number of hits, usually heavily orchestrated (think of Where Did Our Love Go?). I remember seeing it reviewed on Juke Box Jury, and I loved it immediately – faster, bouncing along, the propulsion provided by the genius, James Jamerson, the top Motown bassist (and also Benny Benjamin, the drummer). There is a first shot at recording this now available, and it shows Ross attempting to do her own take on the words. Someone has wisely ushered her further back into the ensemble, where her voice – such a distinctive one – always shines best. This was the first in a run of five singles (culminating in Reflections) which were strokes of Funk Brother genius. (One of my favourite films is the documentary made in 2002, Standing In The Shadows Of Motown, about the backing bands behind the record company’s hits, which is a kind of tribute to Jamerson, who had died shortly before the film was made. It’s what led me to pay attention to Joan Osborne. But I digress.) In his collection of 1001 Greatest Singles Ever Made (1999), Dave Marsh is a little snooty about Diana Ross, but includes this song. He takes time out, correctly, I think, to dismiss Phil Collins’ cover of it a decade or two later: but he doesn’t spot what makes Ross’s voice so distinctive. She changes several of the vowels, more than is strictly necessary. Lurve for love. Mahn for mine. Awn for on. Ah for I. Trurst for trust. Even hengin’ for hangin’. I think this was the start of a process that led to the way most American artists bend the vowels now. A pity, I think. But I still love her voice here.

On its way to No. 2, but still just outside the chart in early September was The Who’s I’m A Boy. This amused me at the time. After all, after Townsend’s falsetto opening, what does Daltrey sing but ‘My name is Bill and I’m a headcase/ They practise making up on my face’? It was intended for a rock opera that Townsend shelved (there is a different version on their first hits album, with a french horn and an additional verse): I never liked the rock opera schtick, and by Tommy, I had given up on The Who. But I like the mad bashing-along of Keith Moon and his drums.  When I saw them first (1969), I was hypnotised by Moon, who was hell-bent on upstaging the others (they were the opening act at Sunderland’s Locarno at the end of July – a venue re-christened ‘The Fillmore North’ by its optimistic manager. It had fake palm trees, a fact not lost on Roger Daltrey, who altered the words of Substitute to accommodate them).

When I saw them first (1969), I was hypnotised by Moon, who was hell-bent on upstaging the others (they were the opening act at Sunderland’s Locarno at the end of July – a venue re-christened ‘The Fillmore North’ by its optimistic manager. It had fake palm trees, a fact not lost on Roger Daltrey, who altered the words of Substitute to accommodate them).

Already heading up through the charts was The Mindbenders’ Ashes To Ashes: since unhooking themselves from the estimable Wayne Fontana, the Mindbenders had had some luck with A Groovy Kind Of Love. They stuck with the same songwriters, Carole Bayer and Toni Wine for this one (no relation to the David Bowie song). It’s rather a jolly melody for a lyric that quotes the funeral service. The Mindbenders featured Eric Stewart, later of 10 cc. But perhaps more noteworthy is that the songwriter (then just 18) was later very successful as Carole Bayer-Sager.

On the way out of the hit parade was Elvis and Love Letters. Elvis had been through a rough patch, with memories of His Latest Flame fading, blotted out by the truly indifferent film soundtracks that Col. Parker had foisted on him. This song was a return to form – a well-known song that depended on great interpretation. It’s a film song from 1945 by Edward Heyman and Victor Young, who won an Oscar with it (the film was also called Love Letters). Heyman’s big number was Body and Soul (he also wrote The Wonder Of You); Young had written My Foolish Heart. This song had been a big hit for Ketty Lester in 1962. Elvis slows the song, and adds great drama; where Lester enunciates, Elvis rumbles – notice how he elides ‘I memorise’. David Briggs, the pianist, was almost overawed, terrified he’d add a bum note – but he later persuaded Elvis to record a vastly inferior version. And his piano playing is actually wonderfully supportive.

Sadly no relation to the Hollies song

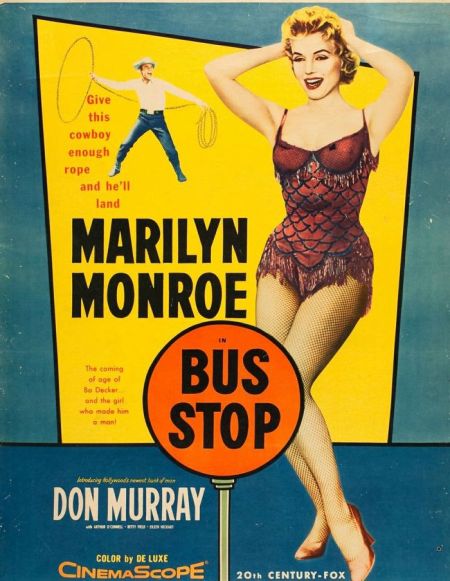

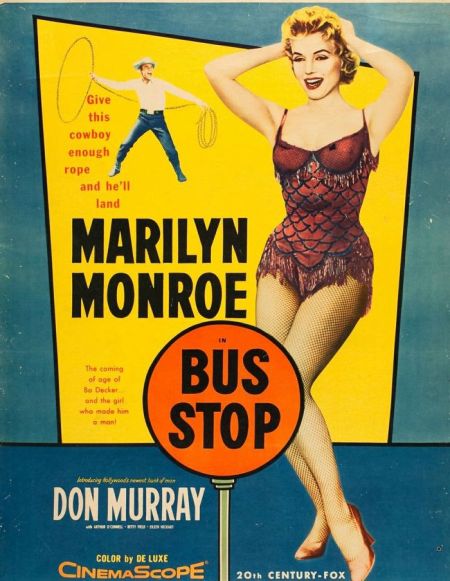

Also leaving was the Hollies’ hit, Bus Stop, written by another future 10 cc-er, Graham Gouldman (he had already given them Look Through Any Window a year earlier). The Hollies were always more skilful than might be expected – the speedy opening of the song resembles the speedy opening of their first single, We’re Through. And the harmonies are terrific. Allan Clarke takes the lead, and you can hear the imitable Hicks and Nash coming in above him. But it is the sheer wrongness of the lyrics that make it so appealing. It’s a strangely formal account of meeting and falling in love at a bus stop under an umbrella. There’s amazing mundanity: ‘sometimes she’d shop and she would show me what she’d bought’ and strange unconversational and inverted asides – ‘that umbrella, we employed it./ By August she was mine’ and even coyness: ‘Someday my name and hers are going to be the same’ (note the disguised rhyme). Oddest is ’employed’ (rhymes with ‘enjoyed’) – even ‘deployed’ might be better! Against these oddly stilted phrases are the everyday phrases sewn into the melody – ‘That’s the way the whole thing started,/ silly but it’s true’, and the elliptical opening ‘Bus stop, wet day, she’s there, I say/ Please share my umbrella/ Bus stop, bus goes, she stays, love grows…’. It is not only fascinating but very singable because each word is so carefully pronounced. (Goldman did a good version himself on a 1968 solo album, and this turns up on some 10cc compilations.) It oughtn’t to work, but it does, and I love the song. I was surprised when it had its hook lifted by Noel Gallagher for the song Ballad of the Mighty I. Maybe words were had…

The final significant leaver was Chris Farlowe’s Out Of Time – the representative of The Rolling Stones here. It was one of the catchier songs on their LP Aftermath (I still think it’s their best, and it is often overlooked these days). Farlowe had covered it for Andrew Loog Oldham’s Immediate label, and taken it to the top of the charts in July (during which week, England won the World Cup). The Stones themselves are said never to have performed this, which seems a pity, although perhaps Farlowe, with his bruiser of a voice, owns it. I encountered Farlowe in 1972, when he was with Atomic Rooster (not a great fit), and played at my university. He was in a bad mood, let’s leave it at that: the only singer we ever had who was! The Stones’ own version has a strange history – three variants have been issued (probably because the first was so long, that is, ‘long’, at 5 mins 36 secs. One of the versions is actually the backing track for Farlowe, with Jagger’s voice restored – it was a demo.

Glossing over the imminence of Winchester Cathedral by The New Vaudeville Band, the song most worthy of mention, outside the Twenty, is Sonny and Cher’s Little Man. This is a most peculiar song, what with its balalaika-style opening, and its Eastern European/ Gypsy beat (not surprisingly it was very popular in Europe). Its lyrics are strange. ‘Catch the sun’ seems to be a euphemism for death, and the come-on to Sonny is ‘You’re growing old/ My mother’s cold’. Dead too? But the chemistry between them really seems genuine, and their double act was memorable, however cheesy. Cher’s voice (like Diana Ross’s) is sometimes a bit off-key, but, also like Ross’s is super-distinctive. I seem to have accumulated all her albums over her fifty-year career – and they are wayward in style, and constantly on the move. I also saw her about ten years ago – a great show-woman. I am almost ashamed to admit (in the context of the French clip I’ve given you) that I liked their style. Outraged friend: You modelled yourself on Sonny? Self: No, Cher. Cher’s voice always stands out, a pleasant foghorn, even in the huge chorus on Be My Baby and You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling, despite Spector’s excesses. Sonny Bono, ten years older than Cher, was hooked on Spector’s sound, and some of their best singles go wildly over the top – try Living For You. However, when Cher branched out, he had to be practically sidelined, as during the production of 3614 Jackson Highway at Muscle Shoals in 1969. (His age is given away in the promo films when he snaps his fingers like one of the Rat Pack!)

Glossing over the imminence of Winchester Cathedral by The New Vaudeville Band, the song most worthy of mention, outside the Twenty, is Sonny and Cher’s Little Man. This is a most peculiar song, what with its balalaika-style opening, and its Eastern European/ Gypsy beat (not surprisingly it was very popular in Europe). Its lyrics are strange. ‘Catch the sun’ seems to be a euphemism for death, and the come-on to Sonny is ‘You’re growing old/ My mother’s cold’. Dead too? But the chemistry between them really seems genuine, and their double act was memorable, however cheesy. Cher’s voice (like Diana Ross’s) is sometimes a bit off-key, but, also like Ross’s is super-distinctive. I seem to have accumulated all her albums over her fifty-year career – and they are wayward in style, and constantly on the move. I also saw her about ten years ago – a great show-woman. I am almost ashamed to admit (in the context of the French clip I’ve given you) that I liked their style. Outraged friend: You modelled yourself on Sonny? Self: No, Cher. Cher’s voice always stands out, a pleasant foghorn, even in the huge chorus on Be My Baby and You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling, despite Spector’s excesses. Sonny Bono, ten years older than Cher, was hooked on Spector’s sound, and some of their best singles go wildly over the top – try Living For You. However, when Cher branched out, he had to be practically sidelined, as during the production of 3614 Jackson Highway at Muscle Shoals in 1969. (His age is given away in the promo films when he snaps his fingers like one of the Rat Pack!)

We arrive, with no fanfare, at the Top Twenty. Reverse order is traditional.

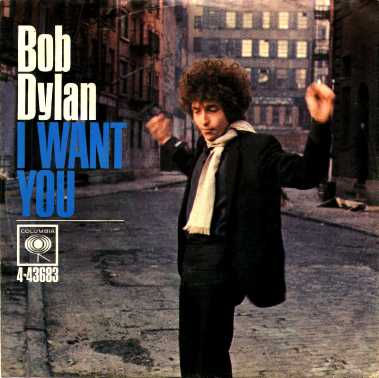

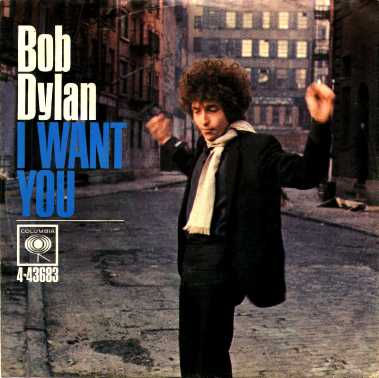

20. Bob Dylan – I Want You

(The images in Youtube are from the film Cinema Paradiso.)

In a way it is surprising to find Dylan anywhere near the Top 20 (this was his last visit till 1969), but it’s a good indication of what a complex and mixed bag the twenty was. This is from perhaps my favourite album (out of all of them, not just Dylan’s) , Blonde on Blonde, and is one of four songs on it that are jaunty, offsetting the slightly dirge-like tone of Pledging My Time, Just Like A Woman, Visions Of Johanna, and so on. It was the last song recorded (three takes) on that album, and is a good example of Dylan being careful to make fun of his sonorous side: ‘The drunken politician leaps/Upon the street where mothers weep/And the saviors who are fast asleep/ They wait for you …’ [but I want you]. It also shows his fondness for casual, triple rhyme: ‘Now your dancing child with his Chinese suit/He spoke to me, I took his flute/No, I wasn’t very cute to him – Was I?/But I did though because he lied/Because he took you for a ride/And because time was on his side’. The drumming (Kenny Buttrey) – a skilful pattering across the skins – is notable. The sound is much thinner, more affectionate, than it had been on Highway 61 Revisited, and Dylan’s restless harmonica is also great. Already, Dylan was moving away from harder-edged rock towards country music (this was cut in Nashville). He also has the confidence to ride a slip of the tongue (about 2 mins 20 secs in) – he often stumbles, and he’s always got a place to fall, as one might say.

19. Lee Dorsey – Working In The Coalmine

‘Cause I make a little money/ Haulin’ coal by the ton/ When Saturday rolls around/ I’m too tired for havin’ fun’. This is a great production by Allan Toussaint of one of his own songs. As he admitted, neither he nor Lee Dorsey had been down a coalmine, but Lee Dorsey, who revived a flagging career with this song, put a nice edge on the lyrics (‘How long can this go on?… Lord I’m so tired’). The sound of pickaxes hitting the rock is what makes it memorable, but, mixed high, what gives the record its propulsion is the bass. The bassist – now 91 – was Chuck Badie. Badie also played on the (even better) follow up, Holy Cow. His jazzy fingers are the key to the success of the recording.

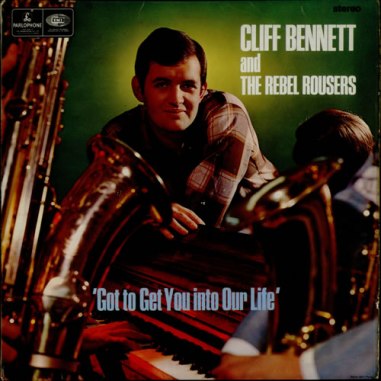

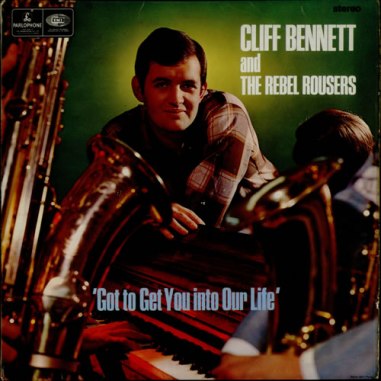

18. Cliff Bennett and the Rebel Rousers – Got To Get You Into My Life

The first appearance by The Beatles. Bennett (still touring, now in his late 70s) was an Epstein signing, and McCartney himself produced this version of the song – I think, one of the best covers of a Beatle song (the original is on Revolver). (But not as good as The Beatles own version!) McCartney has long since revealed it was about marijuana (‘I took a ride, I didn’t know what I would find there’), something nobody would have imagined in 1966. The cover shown is of the album, hence the slight change. It was an unusually brassy single for the time. The Rebel Rousers included Chas and Dave!

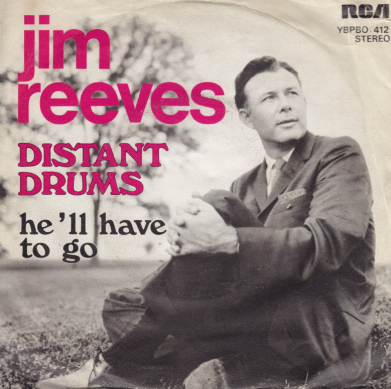

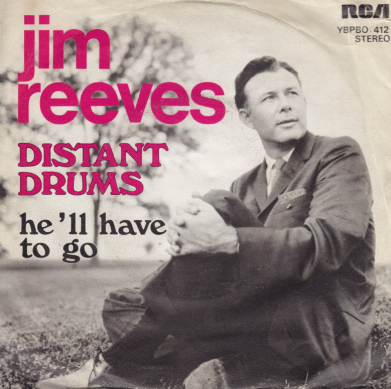

17. Jim Reeves – Distant Drums

Jim Reeves had been killed in an air crash (he was the pilot) about two years before this huge hit (it eventually topped the chart for five weeks, and was still selling in January 1967). It was his only No. 1 hit. In his lifetime, he had had many successes (first charting in 1952 in the USA, and appearing fairly regularly in the UK chart from 1960 onwards), although the only one I recall is ‘I Love You Because’, with its deep bass dip on the word ‘because’. The song had been written by country composer Cindy Walker (You Don’t Know Me, Dream Baby (How Long Must I Dream), Bubbles In My Beer), and had been covered by Roy Orbison. Reeves’s version was rescued from Walker’s private stash, beefed up with an orchestra, and teamed with ‘He’ll Have To Go’, already a hit in 1960. the demography of the record-buying public had changed: parents started copying their children, and bought it in shed-loads. I was once introduced to a friend’s father in Doncaster. He had a huge record collection. It was ALL by Jim Reeves. I recall some proprietorial angst about Reeves being top of the chart, but I also remember singing along. The lyrics are retro: the man wants his girlfriend Mary to marry him, before he is sent across the wild grey sea to fight. He hears bugles, he hears drums. The distant drums might change our wedding date, he moans. A likely story. Still, Andrew Marvell tried the same thing on with his coy mistress, so there is an illustrious antecedent.

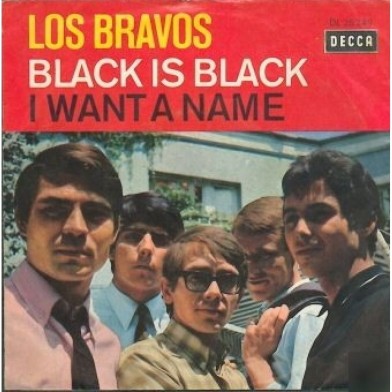

16. Los Bravos – Black Is Black

Perhaps the catchiest bass line after The Animals’ We Gotta Get Out Of This Place, only more danceable. Much was made of the fact that they were the first Spaniards to bother the charts, but the lead singer (still going!) was actually German, and good at Gene Pitney-type strangulated vocals. Franco offered him dual citizenship when they did so well in the charts… It is odd to think of 1966 as a time when right-wing dictators were very much alive and kicking their boots. It’s a jolly beat for a song that thinks desertion has left the singer black, grey and blue. (They dressed in slightly undertaker-ish suits.) It’s hard to dislike this: it is so easy to sing along to while dancing (as I recall).

15. Ken Dodd – More Than Love

Let’s face it, there had to be a massive clunker in here somewhere, and who better than the man who out-sold the Beatles in the 1960s? This is very much one of his most lugubrious light operatic failures. But let’s look at who wrote the song – Norman Newell, who was a top record producer for Columbia; Ernie Ponticelli, who was an EMI plugger, but had been Donald Peers’ accompanist; oh, and Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1837). Newell had also co-written Promises for Dodd (with Tom Springfield).

As for Ludwig, why is he not remembered as Van Beethoven? We don’t speak of Vincent Gogh. Newell and Ponticelli half-inched his melody from Piano Sonata no. 8 (Pathetique), second movement. This was precisely the thing Lord Reith and the BBC cracked down on in the 1940s and 1950s – they hated pop renditions of classics. I suspect Mr. Christelow, my music teacher, would have been with Reith. Let’s move on.

14. Chris Montez – The More I See You

This is an old film song from 1945, and is originally, as sung by Dick Haymes in Diamond Horseshoe, quite a glutinous and dreary song, despite being written by the dependable Harry Warren (I Only Have Eyes For You, That’s Amore, Chattanooga Choo-Choo, 42nd Street, and many others) and Mack Gordon, the lyricist (At Last, You’ll Never Know). Montez had had no hits since 1962, and Let’s Dance and Some Kinda Fun. This was a departure, with its Latino beat, and its up-tempo xylophone. He had a very high voice, and was quite a pudgy-looking man – Youtube has let us down a bit here, as I recall the promo film quite well. He was wearing Bermuda shorts and walking towards the camera out of the Californian waves. I like the air in this – it’s very simply produced, and probably would have been better without the la la las that appear towards the middle of the song. But I like the handclaps. (Montez is still going, although has had no hits since 1972.)

13. Manfred Mann – Just Like A Woman

This is Bob Dylan’s second as-it-were appearance – as noted above, this is from Blonde On Blonde. Manfred Mann (led by the South African beatnik-looking organist of that name) had had several successes with Dylan songs, including If You Gotta Go, Go Now, and With God On Their Side; and they were to have further, huge success with The Mighty Quinn in 1968. But this record was notable because it marked the first appearance of a new vocalist, Mike D’Abo, who had replaced the highly popular Paul Jones. The betting was that MM would sink, and that PJ would prosper. But D’Abo looked and sounded astonishingly like Paul Jones, and many column inches were fretted away on comparisons. The group went on to have several more hits, and Paul Jones didn’t really, although his career with The Blues Band has been entertaining and exemplary. Both D’Abo and Jones regularly appear with ‘The Manfreds’, that is, most of Manfred Mann – but not its eponymous leader. In fact, if we discount Jack Bruce, who passed briefly through the group at about this time, every single member is alive and ready for a reunion – almost unheard of. (The same is actually true of The Hollies.)

It’s not, having said that, a fantastic version – the beat is unsubtle, for a start. The strumming seems too loud after the version Dylan released.

12. The Alan Price Set – Hi Lili Hi Lo

After Alan Price left The Animals in a hurry and with the song-arranger’s income from The House Of the Rising Sun in his bank (boo hiss!), and after a brief appearance in the Pennebaker film about Dylan, Don’t Look Back, during which he sings Dave Berry’s Little Things, he formed a new band. The word ‘Set’ at the time seemed a bit of a throwback. (The band is quite similar in style to Cliff Bennett and the Rebel Rousers.) But they had a brilliant hit with a version of Screaming Jay Hawkins’ I Put A Spell On You, which came out just before the album Animalisms, with Price’s place taken by Dave Rowberry – and which also did a version of I Put A Spell On You. Hi Lili Hi Lo was a 1952 song, taken (like The More I See You) from a film – Lili, starring Leslie Caron. It was sung by Caron and puppets – it’s a kind of pastiche of a German folk-song, rather like Wooden Heart. However, it had been covered by innumerable people – Eve Boswell, Chet Atkins, The Four Seasons, The Everly Brothers, and had even reached the Top Twenty in the UK in 1963 (Richard Chamberlain reaping the rewards of his popularity as Dr. Kildare). More pertinently, it had been on the Manfred Mann album Mann Made the previous year. It was a rollicking and powerful single, featuring the talents of (among others) the trumpeter John Walters – soon to be John Peel’s radio boss – and Steve Gregory, a sideman much in demand, to be found on Careless Whisper by George Michael, too. He also played with Mayall’s Bluesbreakers (the ‘Beano’ album), with the re-formed Animals – and I saw him as part of Ginger Baker’s Air Force in Sunderland in 1970.

11. The Mamas And The Papas – I Saw Her Again

Although Michelle Phillips (now the only survivor of the quartet) sang on this song, she was replaced by Jill Gibson when it was being promoted – the result of an affair with Denny Doherty about which the song was allegedly written (it is credited to her husband John Phillips and Doherty). (This may be why there are no video recordings of it.) It is a popular song with M&P fans, but I preferred the two previous ones (California Dreamin’ and Monday Monday) and the next big one, the cover of the Shirelles’ Dedicated To The One I Love. The harmonies and singing are brilliant, with great washes of sound (too much violin in the bridge): but the melody is not so strong. There is a notorious example of ‘happy accident’ in it – the engineer accidentally included Doherty’s false start (‘I saw her’), and producer Lou Adler liked it so much he kept it in (it’s at about 2.40). The highlight is the descending vocal by Cass Elliot towards the end of the song.

Aren’t the apostrophes on the sleeve irritating? And wrong!

10. The Lovin’ Spoonful – Summer In the City

We are now in the presence of pop genius at last. The promo isn’t what I remember – there was a series of images of the four of them in shimmering heat, jumping down steps. This was not at all what was expected of the Spoonful – normally happy and folk-jug band. This was hard edged, with a – for then – highly unusual use of sound effects. It was written by John Sebastian and bassist Steve Boone, with a steal from Sebastian’s brother Mark and a poem he had written in high school. The drummer Joe Butler and Steve Boone still perform as the Lovin’ Spoonful.

It’s a great song, built on the contrast between the heat of the day and the excitement of night: All around, people looking half dead/Walking on the sidewalk, hotter than a match head. I certainly didn’t get these lyrics when I was 14. It was perhaps their most raucous song, and all the better for that.

9. David and Jonathan – Lovers Of The World Unite

Actually, I’m not keen on this… It’s catchy but I am less than keen on the falsetto, and I loathe the lyrics – a sort of phoney trade union appeal to the amalgamated lovers: Unite! (you alone know what is right). It manages to get even loftier – ‘Man has only he to blame’… Yup! The singers had much more luck as songwriters, since they are Roger Cook and Roger Greenaway, writers of such goodies as You’ve Got Your Troubles, I’ve Got Mine and Long Cool Woman In A Black Dress, but also I’d Like To Teach the World To Sing …

Very shrill.

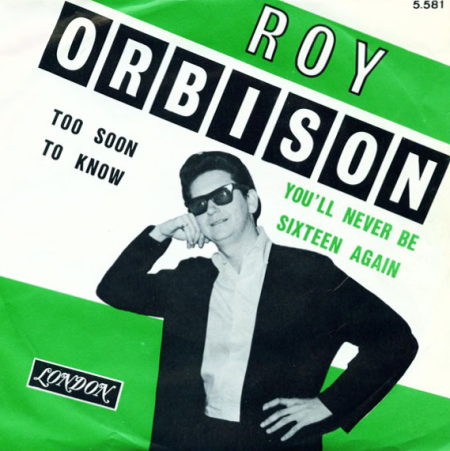

8. Roy Orbison – Too Soon To Know

Everything Orbison does is full of emotion and grace, but there was some controversy with this one. He had completed an album some months earlier called Roy Orbison Sings Don Gibson – this is a Gibson song from 1958, not an Orbison one. Orbison’s version is emotional and pure, far better than Gibson’s, and Orbison’s record company put it out as a single. But there was a thought that it was cashing on the death in a motorcycle accident in June of his wife Claudette. And sure enough, many assumed it was a response to it, what with its sepulchral piano intro. A pity all round, since it is a moving vocal and a sensitive accompaniment – and it was almost the last chart success for the Big O for 15 years.

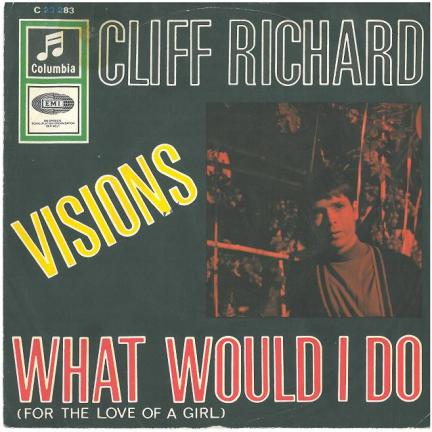

7. Cliff Richard – Visions

Ah, Cliff. At this stage of his career, he had taken to wearing stern black glasses, and appearing on TV to talk about Jesus. In a suit. Cliff, not Jesus. This is the kind of tune which (see the Youtube link) invites views of rolling countryside. Is that a harp or a fancy guitar? Visions of you, in shades of blue... bad poetry. the writer, John Ferris, was better at instrumentals. I used to think I could defend this but Cliff makes it so hard – though I did like Time Drags By, his next one.

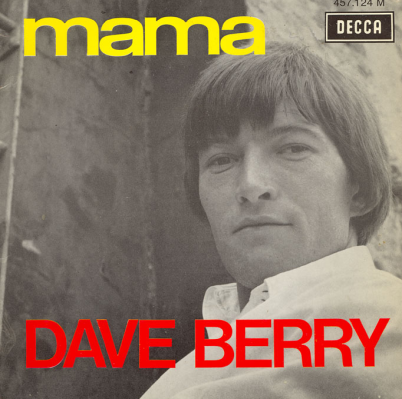

6. Dave Berry – Mama

Dave Berry (whom Alan Price imitates in Don’t Look Back) is still around, is in great shape, has kept working across Europe – and if he sings this song, sings it wryly. It was one of his biggest hits, but it is nothing next to The Crying Game and Little Things. The tune is simple, but the lyrics just too glutinous – ‘Who’s the one that tied your shoe when you were young/ and knew just when to come and see what you had done?’. The song itself, by Mark Sharron, was a steal – it had been a minor success for Sharron’s regular customer, pop-country singer B.J. Thomas, whose biggest hit, Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head, featured incongruously in Butch Cassidy … That had also been nabbed over here – by Sacha Distel, of all people.

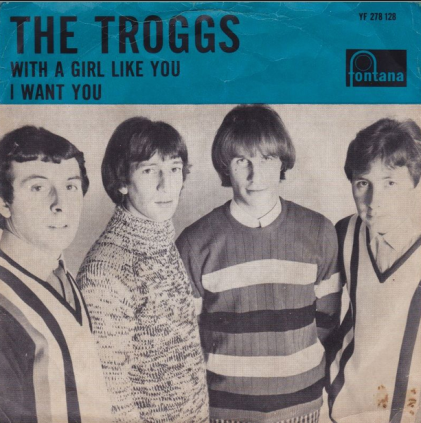

5. The Troggs – With A Girl Like You

The Troggs were from Andover (the guitarist is still trading as the Troggs, although I did once see a version with the late Reg Presley, who was buoyed by the squillions he earned from Wet Wet wet’s cover of Love Is All Around). They were UK hillbillies – desperate semi-pros, so it sounded, who managed a string of hits to everyone’s surprise – the music press of the time wrote them off several times. This is a Presley original, with the trademark ba ba ba ba ba bas in it. Reg, the singer, sang very nasally, and affected a sort of sexiness which made most onlookers laugh. But he had the hooks. Their reputation was made by a tape that circulated of their attempts to nail another single in 1970: a report here.

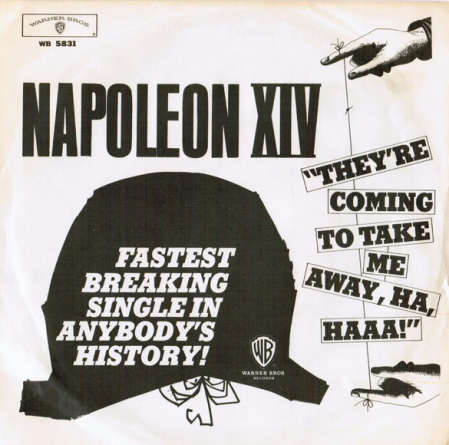

4. Napoleon XIV – They’re Coming To Take Me Away Ha Haaa!

Recording engineer Jerry Samuels took more than six months to write this. He claims to have based the beat on the tune The Campbells Are Coming. See what you think! Believe it or not, there was a ‘response’ record by ‘Josephine XV‘! Novelty records are almost always flashes in the pan, and this one flashed more briefly than most, as it was ordered off most of the airwaves in the USA (it still holds the record for the steepest decline in chart position over one week). Samuels havered about the recording, probably conscious that making fun of mental health was not the best way to proceed – hence, I suspect, the rather silly ‘twist’ (i.e., he is talking not to a woman who jilted him, but his dog). Because most of us had never heard of the ASPCA, and did not then think of dogs as mutts, this was not obvious. All the same, I definitely recall being in a disco and dancing to this … Samuels’ ‘skill’ was to engineer the sound so that his voice speeded up but did not change tempo. Brian Wilson was recording something similar a few months later – he uses the same trick on ‘She’s Goin’ Bald’, a track on the Smiley Smile LP. Perhaps he was copying? Should it have been banned? I don’t know. Banning music is treacherous. I might personally have banned Brown Sugar, but there you go.

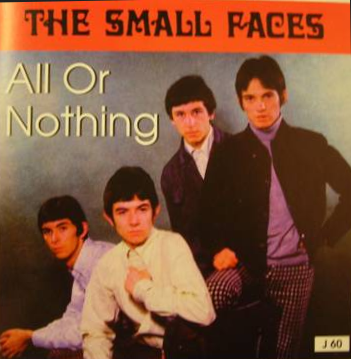

3. The Small Faces – All Or Nothing

The Small Faces themselves rated this song, co-written by Steve Marriott and Ronnie Lane, although I think Tin Soldier is far superior, and a little less ragged. It’s the only good rock song on this list, and would have been a hit ten years later. I am quite taken with the reasoning/ hear a thing rhyme! The star is very much Marriott’s rasping voice – the quiet passage before the storm of the final chorus is also well-timed. The shouted ‘Come on children’ is taken by Marriott, a little incongruously, from pastors crying out in gospel halls. All the same: this is the voice that led to Robert Plant.

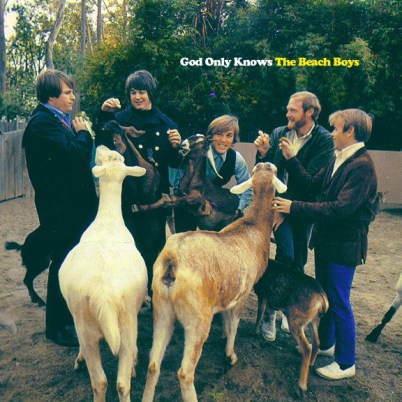

2. The Beach Boys – God Only Knows

This is often voted the best single of all time (Mojo in the 1990s), or thereabouts. It was written by Brian Wilson when he stepped back from touring with The Beach Boys, and co-opted a casual acquaintance, advertising agent Tony Asher, to help him with the lyrics (Asher was the son of silent movie star, Laura La Plante). A lot is made of the fact that it was the first hit single to reference God, although actually, a 1954 single by Renee Hinton (then 17) and the Capris had the same title (and seems to borrow its melody from the same source as The Toys’ A Lover’s Concerto – Minuet in G Major by Petzold, formerly – until 1970 – thought to have been Bach). My point is that I don’t think the ‘God’ caused much bother really. In fact, the lyrics, like many of Beach Boys songs, are folksy-banal. ‘I may not always love you/ But ‘long as there are stars above you…’ – the only thing that lifts this out of a rut is the rhyme of are and stars. ‘If you should ever leave me/ though life would still go on believe me’ – terrible rhyme on leave/ believe – ‘the world could show nothing to me/ so what good would living do me?’ – show nothing to is a very odd construction! But Wilson’s work is in the chord changes and the harmonies. He needs a plain set of almost invisible lyrics, and he gets it here. He works on them by shifting perpetually between major and minor keys – I am not good enough to get any more technical than that…

The lead singer is Carl Wilson, the steady one of the Wilson brothers. We don’t always know who is singing a Beach Boys song, but all of them had their moments – Carl here and on Darlin’, Al Jardine on Help Me Rhonda, Mike Love on Surfin’ USA, Brian Wilson on the B-side here, Wouldn’t It Be Nice (one of the best B-sides ever, and actually the A-side in many countries). Denis Wilson, Bruce Johnston and (later) Blondie Chaplin also had their moments. Their a capella singing (many albums now exist of them singing without the backing track) is startling – and reminiscent of The Four Freshmen, Brian Wilson’s inspiration.

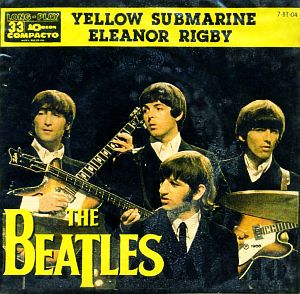

1. The Beatles – Yellow Submarine/ Eleanor Rigby

The double A-side! The Beatles pulled this stroke four times, by my reckoning: Daytripper/ We Can Work It Out, this one, Strawberry Fields Forever/ Penny Lane and (less plausibly) Something/ Come Together. Two songs of different but equal power, two for the price of one, one for the money – one for sheer superiority. It is easy to forget how surprising The Beatles could be. No-one expected a Ringo vocal; no-one expected a song with two string quartets; no-one expected a playground song; no-one expected a single with noises off; no-one expected a really surreal lyric. This single had all these surprises. It was nothing like anything that had preceded it.

The stand-out line in Eleanor Rigby is ‘wearing a face that she keeps in a jar by the door’: the first time that a Beatles single had really aspired to the condition of poetry. Seen in the context of the other songs here, it is a stunning lyric, a snapshot narrative, a song with a clear theme.

Yellow Submarine also features Lennon as the voiceover: Full speed ahead Mr. Boatswain, full speed ahead/ Full speed ahead it is, Sgt./Cut the cable, drop the cable. Yet he didn’t write the lyrics here, on either side of the single. The principal writer in each case was Paul. It is very hard to think of any single by the Beatles where a Lennon song does not feature on one side (or on both sides). This really is McCartney at the height of his game. (The phrase ‘darning his socks’ in Eleanor Rigby is supposed to have come from Ringo. ‘Sky of blue, sea of green’ in Yellow Submarine came from Donovan.) These two songs stand out from the crowd – only I Want You, Just Like A Woman and one or two of the lines in Summer In the City (which also uses sound-effects) run it close.

And there we – a few memories from fifty years ago, and some proof that I have been reading the small print in music magazines for the same length of time. Suddenly this has stretched to 6000 words. I just felt it needed to be explored, and in a largely uncritical way. I can’t defend the original choice, but it is still, at least to me, memorable.

There is a photo of me in Peebles a week later, so this too is 50 years old, a sobering thought. I can’t recall the names of any of the friends I made, but there I am slap bang in the middle, aged fourteen, polo neck at the ready.

Posted by billgreenwell

Posted by billgreenwell

When I saw them first (1969), I was hypnotised by Moon, who was hell-bent on upstaging the others (they were the opening act at Sunderland’s Locarno at the end of July – a venue re-christened ‘The Fillmore North’ by its optimistic manager. It had fake palm trees, a fact not lost on Roger Daltrey, who altered the words of Substitute to accommodate them).

When I saw them first (1969), I was hypnotised by Moon, who was hell-bent on upstaging the others (they were the opening act at Sunderland’s Locarno at the end of July – a venue re-christened ‘The Fillmore North’ by its optimistic manager. It had fake palm trees, a fact not lost on Roger Daltrey, who altered the words of Substitute to accommodate them).

Glossing over the imminence of Winchester Cathedral by The New Vaudeville Band, the song most worthy of mention, outside the Twenty, is Sonny and Cher’s

Glossing over the imminence of Winchester Cathedral by The New Vaudeville Band, the song most worthy of mention, outside the Twenty, is Sonny and Cher’s